Cardiology Tip

Nuances of history and physical exam findings can help distinguish between congestive heart failure and primary respiratory disease in coughing dogs.

In practice, we often evaluate coughing dogs that are also found to have heart murmurs. This can be perplexing, as the character of a cough is often quite similar between the two most concerning possibilities: congestive heart failure (CHF) and primary respiratory disease. Coughing from both of these problems can be harsh, wet, productive, nocturnal, and induced by activity. Severe cardiac and respiratory disease can both result in collapse, exercise intolerance, breathing difficulties, pale gums, and ausculted pulmonary crackles. Thankfully, a nuanced approach to the patient’s history and physical exam may provide clues to distinguish heart versus lung issues.

History details should focus on duration and potential progression of the cough. Coughing from congestive heart failure is typically of relatively recent, even quite acute, onset with relatively quick progression. Families will frequently be compelled to seek help within hours to days, at most a few weeks, after onset of coughing. Dog breeds prone to dilated cardiomyopathy (e.g., Dobermans, Boxers, Irish Wolfhounds) warrant heightened suspicion for CHF with any coughing, as their coughing and heart murmurs can be subtle in spite of severe heart disease with active CHF. Coughing from respiratory disease is a mostly chronic and slowly progressive issue. Families often report the cough has been present for months to years, perhaps even long enough to observe a seasonal fluctuation in severity.

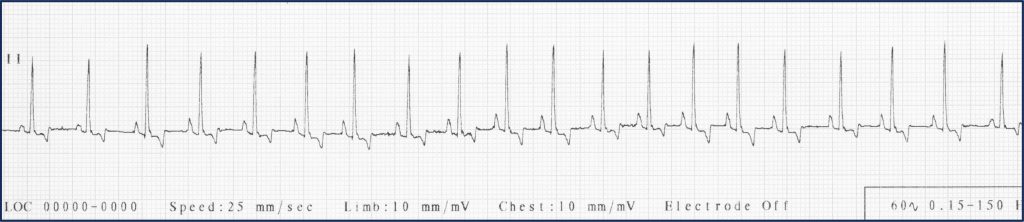

Physical exam findings for body condition score, heart rate, heart rhythm, and lung auscultation can further distinguish between CHF and respiratory causes of cough. Heart failure patients typically exhibit elevated heart rates due to stimulated sympathetic nervous system stimulation. Sinus tachycardia and tachyarrhythmias often occur alongside CHF, and a rapid rhythm that is “irregularly irregular” raises significant concern for atrial fibrillation due to severe heart disease in a coughing dog (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Lead II ECG. Irregularly irregular rhythm consistent with atrial fibrillation.

Body condition score may be decreased for dogs with chronic heart disease that is severe enough to cause CHF, as circling cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-a) contribute to cardiac cachexia. Conversely, dogs with chronic primary respiratory disease are oftentimes of heavier body condition, with the excess intra- and extra-thoracic adipose tissue contributing to respiratory signs. Cardiac auscultation for dogs affected by their lung disease will often yield a sinus bradycardia punctuated by a “regularly irregular” rhythm consistent with a normal respiratory sinus arrhythmia (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Lead II ECG. Regularly irregular rhythm indicative of vagal influence on heart rhythm.

This is due to the high vagal tone that predominates during chronic respiratory conditions. Upon pulmonary auscultation, the presence of crackles alone may not be discriminating, but the context of the crackles may be predictive. Chronic respiratory patients are sometimes found to have marked, diffuse pulmonary crackles despite being relatively eupneic. This is consistent with the chronic and slowly progressive nature of the lung disease that affords the patient time to accommodate to their changing lung function. A patient that develops CHF cannot become accustomed to their accumulating pulmonary edema and would require diuretic therapy for stabilization of respiratory signs.