Tips for Evaluating Dogs With Elbow Dysplasia

Forelimb lameness, whether unilateral or bilateral, in our canine patients can be difficult to assess and seem overwhelming. There are many potential causes of forelimb lameness making the physical examination a very important initial diagnostic tool. Even before the initial examination, the signalment of the patient is paramount in making the correct diagnosis. The age of the dog can greatly aid the clinician, as there are certain disease processes that are more common in the juvenile versus the skeletally mature. The breed can also be an important factor.

Elbow dysplasia is a multifaceted disease that can affect both juvenile and mature dogs, however is more frequently seen in juvenile patients. The disease is a congenital issue and generally affects large breed dogs, however this is not always the case. The complex of elbow dysplasia can be divided into six conditions. One or more of these conditions can cause a varying degree of lameness. The conditions are:

- Fragmented coronoid process (FMCP)

- Medial compartment disease (MCD)

- Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD)

- Ununited anconeal process (UAP)

- Elbow incongruency (EI)

- Ununited medial humeral epicondyle (UMHE)

The sample case here documents the diagnosis of a patient with elbow dysplasia. Emphasis is placed on the hallmark features of the physical examination.

Once a thorough history has been obtained, the first part of a thorough exam is performing a gait analysis. Please view video 1 below looking at the gait of a patient.

Video 1. Young golden retriever dog with left front lameness.

Physical Examination on Dogs with Suspected Elbow Dysplasia

The next step for the clinician is to perform the physical examination. During the physical examination, it is important to palpate the carpus, shoulder, and long bones for any signs of discomfort. For complete evaluation of the elbow joint it is also important to place the joint through full range of motion, from hyperextension to hyperflexion.

Many times, the dog will show some sign(s) of discomfort. It is also very important that the clinician place mild to moderate pressure on the medial aspect of the elbow through the different ranges of motion. With the elbow in a normal flexed/ hyper flexed position and medially placed pressure, the clinician should place the antebrachium in supination. Most dogs with medial compartment disease/elbow dysplasia will experience discomfort with this maneuver. Below is a demonstration of the evaluation (Video 2).

Video 2. A complete examination is critical to aid in the diagnosis of suspected elbow dysplasia. Note the pain when pressured is placed on the medial aspect of the joint.

Diagnostics

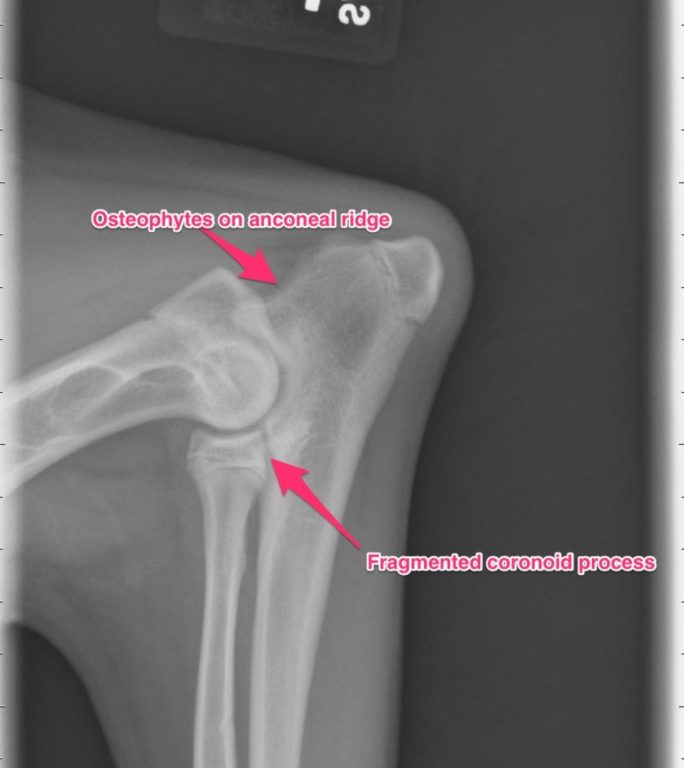

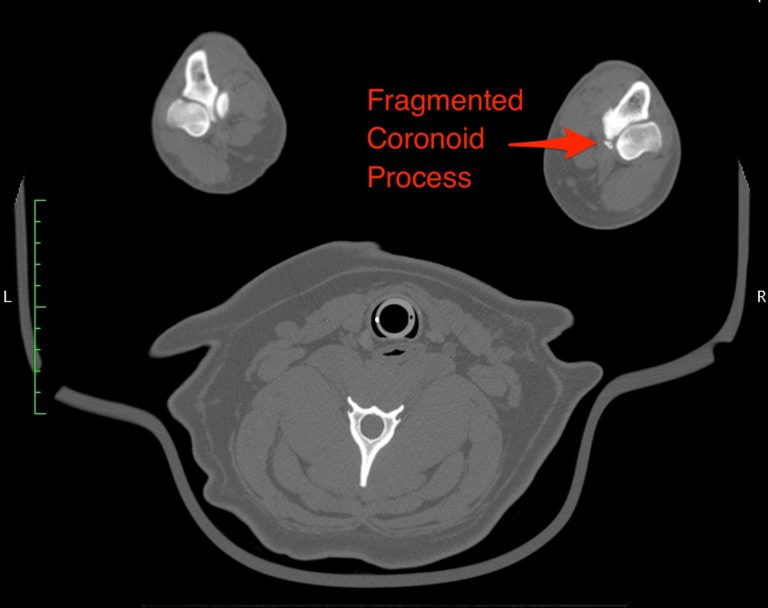

Once the clinician is confident in their physical examination, he/she must then recommend the next step, which typically include some form of imaging. Radiographs (Figure 1 and 2) are most commonly pursued. However, in some patients where one is convinced of elbow discomfort and they fit the criteria for elbow dysplasia (breed and age), one may skip radiographs and recommend sedation with an elbow CT scan (Figure 3). In most young, healthy dogs an orthopedic CT scan can be performed with heavy sedation (reducing cost to the client).

The diagnostic yield of a CT scan is much greater than standard radiographs. Additionally, radiographs and/or a CT scan will generally provide enough information to allow the clinician to recommend further treatment, however there are times when a diagnosis is unclear, and therefore may require further diagnostics such as arthrocentesis with fluid analysis and culture.

Figure 1. Lateral radiograph of the elbow on a dog with foreleg lameness. Note the osteophytes on anconeal ridge and fragmented coronoid process.

Figure 2. Anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph of the elbow on a dog with foreleg lameness. Note the OCD lesion (red arrow).

Figure 3. CT of front leg of a dog with foreleg lameness. Note the Fragmented Coronoid Process.

Treatments for a Dog with Elbow Dysplasia

Elbow arthroscopy is generally the next recommendation for a patient diagnosed with elbow dysplasia. This will provide both diagnostic and treatment value. Arthroscopy allows the clinician to fully assess the cartilage surfaces and allow for full evaluation. It will also allow for removal of fragmented coronoid processes (FMCP) if present (See Video 3).

Video 3. Arthroscopy showing a dog’s elbow with a fragmented coronoid process (FMCP).

The removal of FMCPs will generally improve comfort for the patient. Unfortunately, elbow dysplasia is a lifelong disease and in most cases is progressive with development of further cartilage changes and development of osteoarthritis. In my opinion, a multi-faceted treatment of surgery and aggressive rehabilitation with medical management will yield the best results long term.

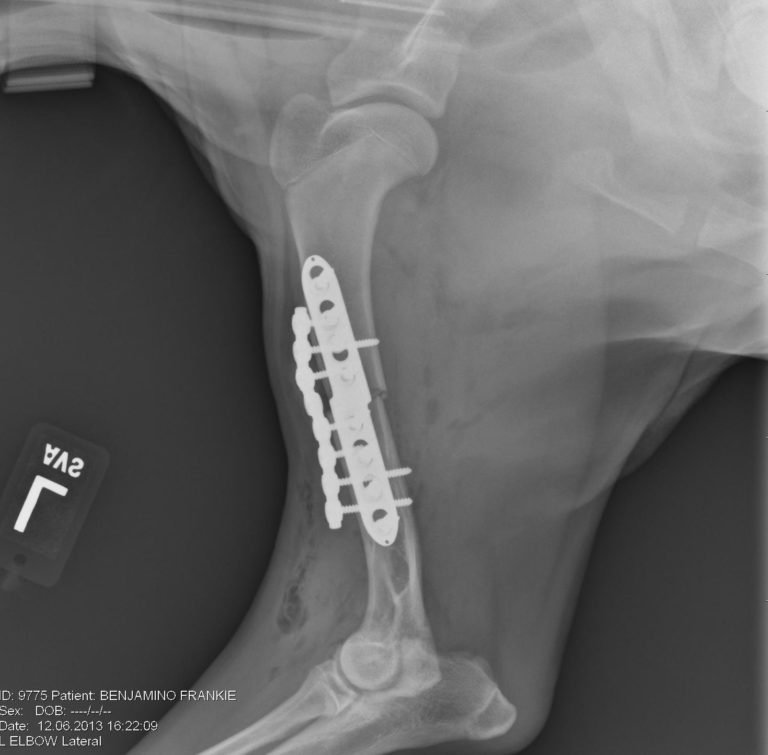

There are other advanced procedures that can have benefit in the correct patient. The primary three advanced procedures are 1. sliding humeral osteotomy (SHO) [Figures 4 and 5], 2. proximal abducting ulnar osteotomy (PAUL), and 3. canine unicompartmental elbow (CUE) procedure. Most of these procedures involve the shifting of pressure and weight to the lateral aspect of the elbow joint, as this compartment is not generally affected by elbow dysplasia. Both CT evaluation and elbow arthroscopy is recommended to confirm a patient is a candidate for these advanced procedures.

The canine elbow replacement is another procedure option, however it has a mixed outcome and has not proven to be as reliable as other joint replacement procedures such as the total hip replacement.

Although there are no comparative studies looking at these procedures against one another, it is my belief that they all have their place in the management of elbow dysplasia.

Figure 4. Lateral radiograph of the left front leg after sliding humeral osteotomy (SHO).

Figure 5. Anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph of the left front leg after sliding humeral osteotomy (SHO).

It is also worth noting we find ourselves in the infancy of veterinary regenerative medicine. While anecdotally, therapies such as platelet rich plasma and stem cell therapy show promise, there remains a void of peer reviewed, objective research. At MedVet, these cutting-edge therapy options are available to our patients. We also actively participate in innovative research to enhance knowledge in the veterinary community. Our experience thus far indicates there is a bright horizon for these new therapies.

Prognosis

With a comprehensive, multimodal approach to elbow dysplasia (arthroscopy, rehabilitation, and medical management), we can expect 80-85% of cases to respond favorably to therapy. This is in the young patient and does not take into consideration patients with extensive degenerative changes and limited range of motion. The remaining 15-20% of patients may require one of the aforementioned advanced procedures (SHO, PAUL, or CUE) or more extensive rehabilitation.

As mentioned above, since this is a hereditary problem we will continue to see degenerative changes in all patients, however in most cases we can dramatically improve their quality of life. See Video 4 of Frankie after surgery.

Video 4. Frankie 2 years after bilateral elbow arthroscopy, bilateral sliding humeral osteotomies (SHO).