Diagnosis and Treatment of Tracheal Collapse in Dogs

Tracheal collapse is most common in middle aged to older small breed dogs with the Yorkshire terrier, Pug, Chihuahua, Poodle, and Maltese being over represented. The condition can be congenital but is often caused by progressive generative changes of the tracheal cartilages (tracheomalacia) leading to a loss of tracheal integrity and a subsequent reduction of tracheal diameter. This loss of tracheal diameter leads to clinical signs including the classical ‘goose-honk’ cough, exercise intolerance, inspiratory and expiratory dyspnea, and cyanosis to name a few.

Diagnosis of Tracheal Collapse in Dogs

Tracheal collapse can often be diagnosed based on a combination of signalment, clinical signs, and thoracic radiographs. If tracheal collapse cannot be captured on plain radiographs then bronchoscopy (Figure 1) or fluoroscopy may be needed to evaluate for a dynamic collapse. Other disease processes such as obesity, inhaled irritants, infectious agents, periodontal disease, recent intubation, cardiomegaly, bronchitis, and parenchymal pulmonary disease (e.g pulmonary fibrosis) must be evaluated as contributory factors and corrected if possible.

Figure 1. Bronchoscopic view of dynamic tracheal collapse in a Maltese.

Treatment of Tracheal Collapse in Dogs

Treatment of tracheal collapse is first geared toward medical management with anti-inflammatory steroids, cough suppressants, and sedation as needed. Bronchodilators are commonly used but likely show minimal benefit with solely tracheal disease present. Prednisone is often the first line corticosteroid with a general starting dosage of 0.25-0.5 mg/kg PO q 12 h until control is noted. Once the cough is controlled, a gradual taper can be considered. Hydrocodone (0.25 mg/kg PO q 8-12 h) and diphenoxylate atropine (0.2 mg/kg PO q 12 h) are the most common cough suppressants. Diphenoxylate atropine often provides a marked improvement but can be used together with hydrocodone if needed. Theophylline (10-15 mg/kg, PO q 12 h) is often used most commonly as a bronchodilator. Inhaled bronchodilators such as albuterol can also be utilized and tends to have fewer side effects than does theophylline. It has been shown that nearly 70% of patient’s signs can be controlled with weight loss and medical management as outlined above.

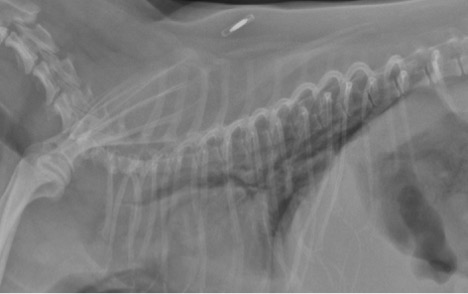

If medical management fails long term or is unable to alleviate a crisis then more aggressive measures such as tracheal rings (extrathoracic collapse) or a tracheal stent can be considered (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Marked tracheal collapse in a Yorkshire terrier pre stent placement.

Figure 3. Yorkshire terrier as in figure 2 post stent placement.

A stent is a self-expanding nickel titanium alloy mesh net designed to maintain the integrity of the tracheal diameter and alleviate respiratory distress. It is important to note patients with stents will often need to be on anti-inflammatories and cough suppressants for life as the stent will not prevent the cough from recurring. With this said, the cough is often better with a stent or can be more easily controlled with traditional measures. As a whole, stents are relatively well tolerated with potential side effects including granuloma formation at the cranial extent of the stent, stent migration, and stent fracture. Although tracheal collapse is a chronic process with life threatening potential, many patients can do well long term with medical management alone or in combination with placement of a tracheal stent, if needed.