When I was asked to write about a topic for the upcoming MedVet newsletter, I knew I wanted to write about Glaucoma because it occupies a lot of my time lately (more about that later). Here I was, contemplating the current state of glaucoma, after a long day of glaucoma cases, sitting at an empty Word document, considering turning in a single page, with 54 font type, “Glaucoma, the story that always ends in blindness. The end.” But I didn’t of course. What I have provided here is an overview of glaucoma, current treatment options, and where we are headed in the future of glaucoma within veterinary ophthalmology.

What is Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is a disease entity that results in damage to the retina and the optic nerve, and thus it often ends in blindness in our patients. But there is much more to it. Glaucoma cannot be molded into a cookie-cutter disease in its etiologies, diagnosis, and treatment options, but there are some things we hold as “truths”.

I usually describe the eye to clients as a sink – there is a tap (the ciliary body) and a drain (the iridocorneal angle). Unfortunately, however, the sink (the eye) is a closed system with a single drain. In the state of glaucoma, pressure occurs because aqueous humor has accumulated in the sink with nowhere else to go. The aqueous humor always accumulates because the drain clogs. Here is where our detective work comes in and what can help determine the prognosis and best treatment plan for the affected eye and the unaffected eye – we must ask ourselves, why did the drain clog?

The type of glaucoma is imperative to successful treatment. But what do we define as success? I told you already this story ends in blindness. But here’s the truth – not always! Early intervention will prolong the time to vision loss. And in some pets, that time to vision loss exceeds their life expectancy. And then there’s those that are misdiagnosed and never had glaucoma to begin with.

Diagnosis of Glaucoma in Dogs

Glaucoma can be considered when the intraocular pressure is over 25 mm Hg. Notice the key choice of word – considered. There are many factors in accurately measuring the intraocular pressure and it is very easy to obtain a false reading if the patient is young, is squinting because of other ocular disease, is brachycephalic, or if your assistant is struggling to keep the patient still. When you feel an accurate pressure has been obtained, look at the eye. REALLY LOOK at it – do you believe the intraocular pressure? A pressure of 25 in an eye with severe conjunctival hyperemia, diffuse corneal vascularization, or with diffuse corneal edema, likely has something else wrong with it. Treat the patient, not always the number, but respect the number. Include it as a possibility, but keep looking, or refer it. Having said that, it is always better to err on the side of caution, treat and/or refer. But treat appropriately and don’t give the patient the gloomy diagnosis and discuss eventual blindness with a client unless you’re 100% certain.

Types of Glaucoma in Dogs

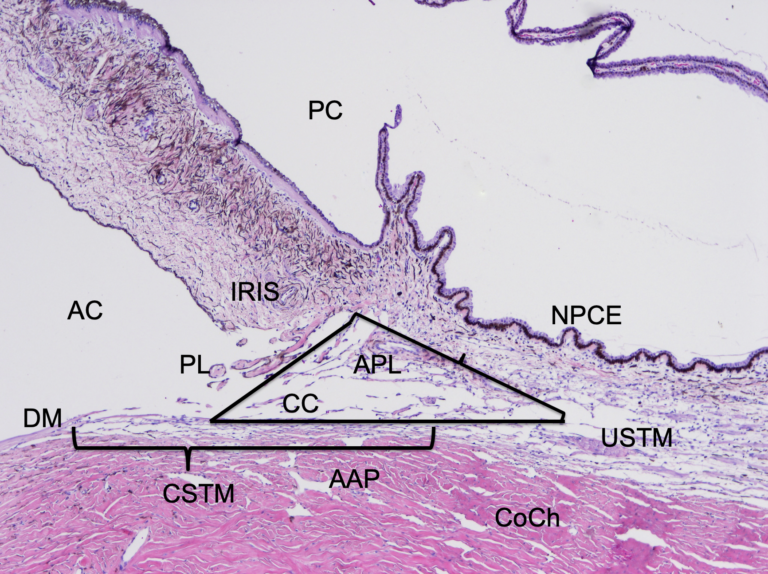

Glaucoma is broadly categorized into “primary” and “secondary”. In ophthalmology residencies we learn about the nuances of “open angle” and “closed angle”, and all about the ciliary cleft; the pipes in your wall beyond the sink’s drain (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Normal canine iridocorneal angle. Aqueous humor (AH) is made by the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium (NPCE) and is pumped into the posterior chamber (PC). AH percolates through the pupil (not shown), into the anterior chamber (AC). The pectinate ligament (PL) runs from the iris base to the terminus of Descemet’s membrane (DM). The PL is the anterior limit of the ciliary cleft (CC), spanned by accessory pectinate ligaments (PL), into which all AH flows. From the CC, most AH exits the globe through the corneoscleral trabecular meshwork (CSTM) and into the angular aqueous plexus (AAP) and collector channels (CoCh) in to scleral venous circulation. This is the conventional pathway. Some AH continues posteriorly, through the uveoscleral trabecular meshwork (USTM) and into the systemic circulation via the supraciliary and suprachoroidal spaces (not shown). This is nonconventional outflow. The cornea is to the right. 4x, HE.

To teach you all the ins and outs of that requires three years with me and studying books containing multiple volumes. But you don’t have time for that, and in veterinary ophthalmology currently, it does not change our course of action. So, we are going to keep this simple, and stick to our “truths” –primary glaucoma is an inherited closure of the drain. When I say “glaucoma” what breeds do you think of? Bassett Hound, Beagle, Siberian Husky, American Cocker Spaniel, Sharpei, Shiba Inu, the list goes on and on. These dogs are usually 3-7 years of age, with one eye that develops glaucoma, but unfortunately the other eye is often not far behind.

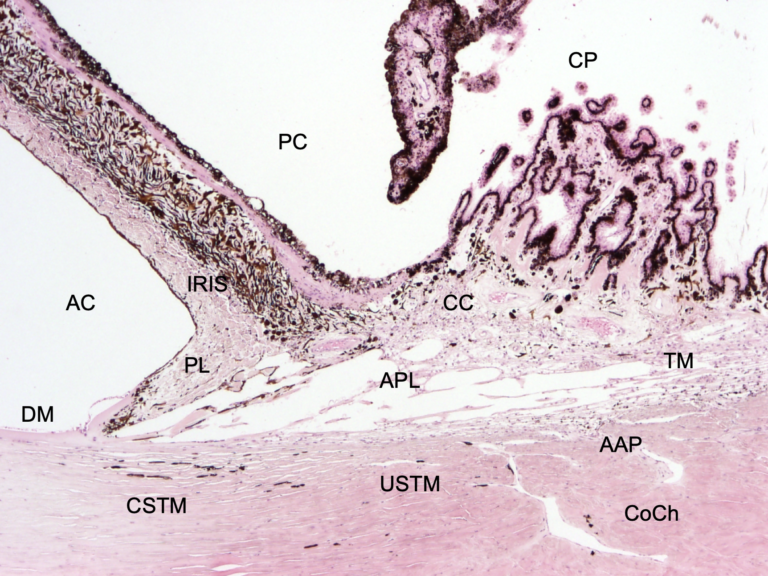

How do we ophthalmologists diagnose primary glaucoma? Gonioscopy can be performed to evaluate the iridocorneal angle for goniodysgenesis (Figure 2), but if we consider our sink analogy, it only allows visualization of the drain (the iridocorneal angle), not the pipes in the wall (ciliary cleft).

Figure 2. Iridocorneal angle with goniodysgenesis (GD), but without elevated IOP/glaucoma. Note the thick pectinate ligament (PL) extending from the iris base to the terminus of Descemet’s membrane (DM). DM is frayed, and overrides the insertion of the PL. The ciliary cleft (CC) is still open, and the other structures of the iridocorneal angle are apparent. CSTM – corneoscleral trabecular meshwork; USTM – uveoscleral trabecular meshwork; U< – uveal meshwork; AAP – angular aqueous plexus; APL – accessory pectinate ligaments; USTM – uveoscleral trabecular meshwork; CoCh – collector channels; AC – anterior chamber; PC – posterior chamber; CP – ciliary processes. 4x, HE.

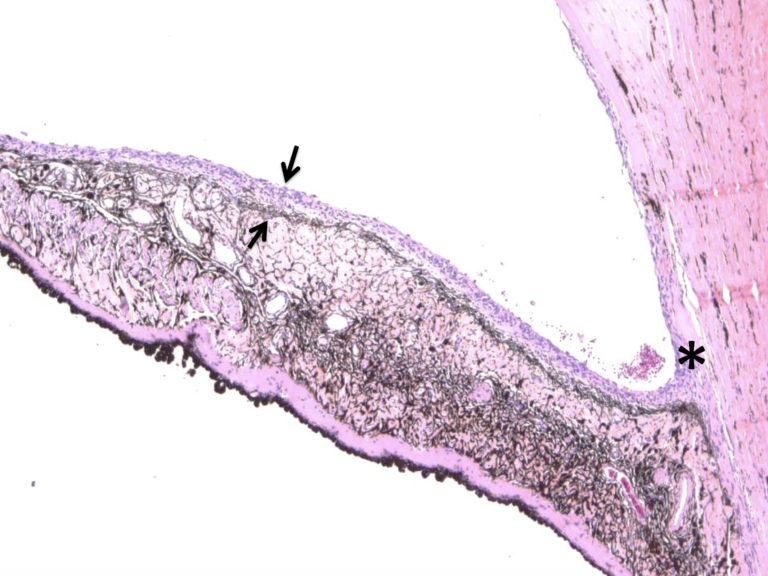

For most ophthalmologists, primary glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion – we rule out causes of secondary – chronic uveitis, lens luxation, retinal detachment, and intraocular neoplasia. We also ensure the signalment of the patient fits with primary glaucoma. The anatomic pathognomonic diagnosis comes with histopathology where the entire drainage system is evaluated for structure, or lack thereof; and again, looking for signs of secondary glaucoma with the presence of a preiridal fibrovascular membrane (PIFM) (Figure 3). Primary glaucoma carries a poor long-term prognosis. Our interventions with medical and surgical therapies only give us time – time with pressure control, time with vision, and time with comfort. The mainstay of therapy depends on what stage the glaucoma is diagnosed and the client’s goals.

Figure 3. Preiridal fibrovascular membrane. The arrows delineate a fairly thick preiridal fibrovascular membrane, which can be seen over the surface of the iris. The anterior iris face is lined by a more or less contiguous band of melanocytes (except in blue eyed animals), which can aid in identification of these membranes. In this case, the membrane has reflected onto the peripheral cornea, forming a synechiae, leading to impaired aqueous drainage, increased IOP and glaucoma. This type of glaucoma is sometimes referred to as neovascular glaucoma, due to the vascular membrane.

Treatment of Canine Glaucoma

With IOP <35 mm Hg and vision still intact, a topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAI) is usually prescribed. Topical CAIs include dorzolamide and brinzolamide. Oral CAIs such as methazolamide, are still available but have become cost prohibitive for most owners. Topical CAIs for dogs should be prescribed TID for therapy. When primary glaucoma is diagnosed, and the other eye is still in its normal state, BID is prescribed. I always cringe when I see the word “prophylactic” or “preventative” used when dealing with glaucoma. If glaucoma is going to occur in the other eye, it is going to happen no matter when or how we intervene. What we are doing is prolonging the time until glaucoma develops, by using topicals early, following IOPs more often, and having the owner visibly evaluate the eye daily as they apply medications.1

With an IOP >35 mm Hg and our first suspicion of glaucoma, we need to critically evaluate for causes of secondary glaucoma, especially intraocular neoplasia and lens luxation before moving to the more potent therapies which include prescribing a prostaglandin analogue, with the aforementioned CAIs, or we consider laser surgery (more on that later). Notice I used the word WITH. Yes, this does mean both medications. The most common prostaglandin analogue utilized in veterinary medicine is latanoprost. Other types include bimatoprost and travoprost.

In human medicine they are utilized once a day, but in our patients, they are most effective BID, and sometimes are needed TID. But let’s go back to the beginning of this paragraph – intraocular neoplasia and lens luxation need to be ruled out before prescribing prostaglandin analogues. Prostaglandin analogues are just that – mimickers of inflammation – effective with a side effect of miosis. In cases of uveitis or intraocular neoplasia, they can have the opposite desired effect causing an increase in intraocular pressure. In lens luxation because of the resulting miosis, the lens will become further trapped in the anterior chamber, causing a significant rise in IOP and pain. In summary, do not prescribe a prostaglandin analogue unless you can guarantee the lens is not anteriorly luxated.

Learn more about the History of Endoscopic Cyclophotocoagulation at MedVet.

When the pressure continues to rise in the face of primary glaucoma therapy, and vision is still present, the owner then faces the difficult decision whether to pursue glaucoma laser surgery or not. If laser is not pursued, we know the beginning of the end of vision is near. How near depends on how high the pressure is rising and how much preexisting optic nerve or retinal damage has accrued over time.

When all other therapy options have been pursued, with the pressure rising over 40 in the face of blindness, we have to consider the patient’s comfort. End stage glaucoma is treated with either enucleation, intrascleral prosthesis, or chemical ablation. Enucleation is the simplest for the patient and the client. With utilization of a CO2 laser at MedVet, we can provide treatment as an outpatient procedure with minimal intraoperative hemorrhage and less postoperative pain. Histopathology on enucleated globes is gold standard postop to confirm the clinical diagnosis and rule out secondary glaucoma. Prosthetics are offered for clients interested in a cosmetic outcome, and chemical ablations for clients with cost constraints still committed to trying to make their pet more comfortable.

The Vision for Animals Glaucoma Consortium: Understanding and Care for Glaucoma

Over the years, MedVet Columbus has become the premier facility for glaucoma therapy and receive referrals from other ophthalmologists from around the country, and this is why glaucoma takes up a lot of my time. In 2017, I was approached by the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists Vision for Animals Foundation to participate in a Glaucoma Think-Tank. Select researchers, MD ophthalmologists, veterinary pathologists, and veterinary ophthalmologists were brought together to discuss glaucoma. After a long day in a conference room we came out with a lot of questions, still not a lot of answers, and a “white paper” on canine glaucoma is in the process of publication. After the Vision for Animals Think-Tank experience, maybe because of my consistent lack of ability to say “no”, but I like to think because of my experience with glaucoma and glaucoma therapy, I was asked to chair a Glaucoma Consortium. So here I am, the chair for the Vision for Animals Foundation Glaucoma Consortium. A big title with lofty goals. The Glaucoma Consortium is comprised of veterinary ophthalmologists both in private practice and academia with pathologists and molecular researchers. Our short-term goals are to create a glaucoma database for clinical data compilation and research. We will create controlled clinical trials for therapeutic and surgical treatments for glaucoma. We are collecting genetic data and globes enucleated due to glaucoma for research.

What do we hope to gain? Better breeding practices, determination of risk factors and treatments that cure glaucoma. It’s going to take a lot of work, but as always, we are up for the challenge. What can you do? Help us lead specialty glaucoma care for pets: discuss glaucoma with your clients, encourage referral early, and participate in clinical trials to come.

Key Points in Canine Glaucoma Therapy

- The cause of glaucoma (primary vs. secondary) is imperative for an appropriate treatment plan as well as prognosis for the affected and unaffected eye.

- Medical therapy for primary glaucoma involves carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and prostaglandin analogues.

- Never prescribe a prostaglandin analogue (i.e., latanoprost) if you cannot guarantee there is no lens luxation.

- When end stage glaucoma sets in and enucleation is pursued, always submit the globe for histopathology with microscopic description of the iridocorneal angle. The cause of glaucoma can be verified and the prognosis for the other eye determined if primary glaucoma is diagnosed.

References

- J Am Anim Hosp Assoc.2000 Sep-Oct;36(5):431-8. The efficacy of topical prophylactic antiglaucoma therapy in primary closed angle glaucoma in dogs: a multicenter clinical trial. Miller PE, Schmidt GM, Vainisi SJ, Swanson JF, Herrmann MK.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Dr. Chris Reilly of Insight Veterinary Specialty Pathology for images. www.insightvsp.com and Dr. Dineli Bras of Centro de Especialistas Veterinarios of Puerto Rico for the endolaser video.