I was recently referred an adult Samoyed that presented to us for her hair falling out. She was not itching or scratching more than what the owner felt was normal. The extent of hair loss and ease of epilation of the hair coat was striking. The hair literally fell out in my hands when touched. The skin was smooth to mildly scaling, and moderately erythematous (red). The pet owner was not affected, and none of the other dogs or cats in the home were symptomatic. The dog had previously been healthy and never had a skin problem. The dog was on several immunosuppressive medications for an immune mediated blood disorder that was diagnosed 2-3 months prior to presentation. This might have been masking any itch that the mite would typically be causing. The dog had also been empirically treated with antibiotics due to a possible superficial bacterial folliculitis, but this did not improve the skin condition.

Diagnosis of Cheyletiellosis

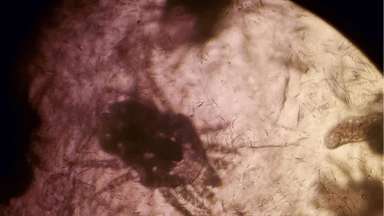

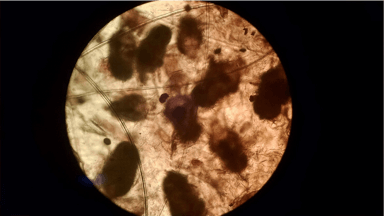

During the consultation and after the dermatologic examination, my initial thought was that the hair cycle and skin integrity had been compromised by the appropriate but chronic use of a glucocorticoid (prednisone). I talked with the pet parent about effects of glucocorticoids on the skin and hair cycle. The veterinary internist caring for the dog had already begun to taper the immunosuppressive medications. I advised, with time, the cutaneous changes from prednisone typically normalize and that I would expect hair regrowth. However, because of the findings on examination and the history of prednisone usage, I recommended a few diagnostic tests to rule in/out some other differentials that can cause the problem the dog was having. Skin surface cytologies were performed to examine for yeast and bacteria. Surface and deep skin scrapings were performed to examine for surface and follicular mites. The differential I was aiming to rule out was canine demodex. Glucocorticoids may proliferate Demodex canis and the clinical exam. Cytologies were negative for bacteria and yeast, but, to my surprise, I recovered the ectoparasite below on skin scrapings.

“Walking dandruff” or Cheyletiella dermatitis is not a common parasite, but we cannot forget to consider this mite as a cause of certain clinical signs. It is rarely diagnosed due to the prevalence of dogs and cats treated consistently with typical flea and tick topical products. Cheyletiella mites are large. Typically, the mite causes a large, dry-appearing scale that can be observed moving. It may affect dogs, cats, rabbits, and humans. The three species of Cheyletiella may affect various host species. Cheyletiella yasguri is found on dogs. C. blakei is found on cats. C. parasitivorax is found on rabbits. The mites do not have much host specificity. All can also affect humans in contact with the infested animal. Skin scrapings, direct examination of the animal with a magnifying lens, and fecal examinations are techniques that may be used to diagnose Cheyletiella. The accessory mouth parts and the palpi that end in hooks are characteristic. Each species has a differently shaped sensory organ that is used to speciate the mite. Free living cheyletids can also affect dogs and cats. These are not reported to produce clinical signs. Cheyletiella live in the keratin layer of the epidermis and are not associated with the hair follicle like demodex. They move around in pseudotunnels in skin debris. The entire life cycle is completed on the host in 21 days. Cheyletiella is an obligate parasite, and the life stages die soon after leaving the host. Adult female mites may, however, live off the host for about 10 days. Eggs shed into the environment with shed hair may be a source of reinfestation. The mites are contagious to other animals and humans.

Cheyletiellosis Signs in Dogs and Cats

Signs in dogs and cats vary. The first observation may be a dry scale on the dorsum (top of trunk) with little itch. Over time, intense itch may develop. The differential diagnoses depend on clinical signs. If scaling is the only problem, a primary seborrhea, intestinal parasitism, poor nutrition, demodex, otodectic mange, pediculosis, and flea exposure should be considered. If intense itch is noted, sarcoptic mange, flea bite hypersensitivity and cutaneous adverse food reaction should be on the list.

Treatment of Cheyletiella Dermatitis

Treatment of Cheyletiella dermatitis can be successful with application of pesticides to all cats and dogs in contact with the mites. Product selection and how it is administered depends on the safety of the product, species being treated, age, hair coat and other concurrent medical problems. Lime sulfur dips or flea products with acaricidal activity are usually effective. Fipronil spray or a spot-on fipronil are effective. Selamecitn (Revolution®, Zoetis) applied topically every 2-4 weeks is effective. Ivermectin and milebemycin may be considered (dogs). Environmental treatment is not necessary, but we recommend basic home environment clean up. If there is a failure to resolve ensure proper application of the product used, consider resistance of the mite to the product selected, consider nasal sequestration of the mites, or reinfestation from the environment or an untreated animal. In some situations, an environmental spray may be needed.

The patient reported here was treated successfully with 3-4 applications of selamectin (Revolution®, Zoetis). The referring veterinarian prescribed the same treatment for the other pets in the home. I advised that the owner maintain year-round use of Revolution® in effort to prevent reinfestation.

Below are images of the mites recovered from our patient. Speciation was not possible with the images taken.