Seizures are a common clinical sign in many diseases of the brain. In broad terms, the etiology of a seizure falls into three general groups: idiopathic (sometimes referred to as ‘primary epilepsy’), reactive (in response to a metabolic disturbance or toxin), and structural (cause by cerebral pathology).

In any patient presenting for recent onset seizure activity, there is one critical question that should be answered during initial evaluation: “Are there any signs of reactive or structural brain disease?”. The answer will help guide decision making regarding further diagnostics and treatment. In senior pets over seven years of age, this question becomes increasingly important due to a higher prevalence of intracranial neoplasia within this population. It is important to remember, however, that an equally large portion of this population can also have idiopathic or primary epilepsy. In fact, studies have reported anywhere between 23-45% of cases of new onset seizures in senior dogs will be diagnosed with primary epilepsy. (Ghormley et al. 2015) Diagnostics therefore are important in these cases to determine the underlying cause and most appropriate treatment.

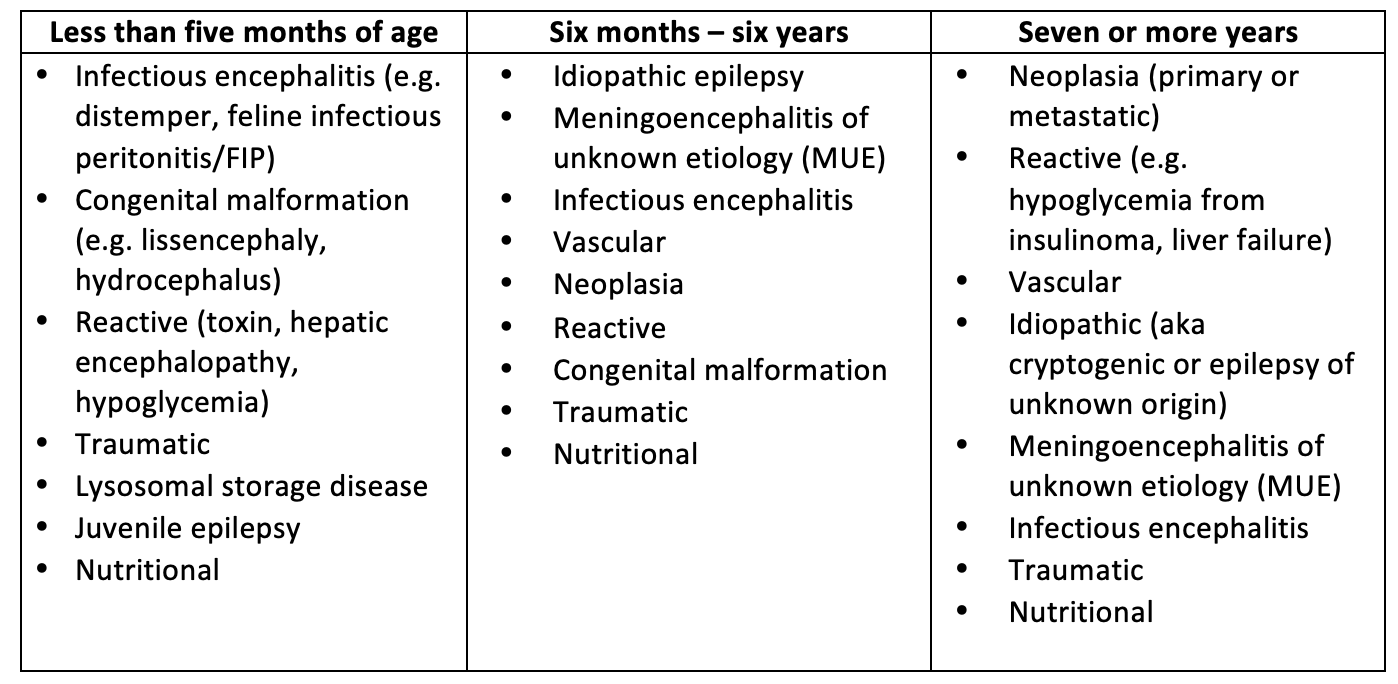

Age may also affect the prevalence of co-morbidities, the degree to which clients are willing to pursue diagnostics, and treatment strategies. The goal of this article is to outline a practical approach to examination and treatment of senior animals presenting for new onset seizures. See Table 1 for a differential list for seizure etiology according to age group.

Signalment

An accurate and complete history is essential to guide clinical reasoning. This starts by considering signalment. Age and breed have been shown to be correlated with prevalence of certain disease types.

- Meningoencephalitis tends to occur most commonly in young to middle age dogs while neoplasia is more commonly found in dogs > 5-7 years of age and cats greater than 10 years of age.

- Idiopathic epilepsy is a common cause of seizures in animals between six months to six years. Multiple studies, however, have found a large population of dogs in older age groups also being diagnosed with idiopathic epilepsy; in these groups the terms epilepsy of unknown origin or cryptogenic epilepsy have been used to note the higher concern for underlying but undetectable structural or metabolic disease.

- Intracranial neoplasia has been shown to have breed correlation: there is a higher incidence of meningioma in older (> 8 years) dolichocephalic breeds and Boxers while gliomas are more common in middle age to older (> 5 years) brachycephalic breeds such as Boston Terriers, Bulldogs, and Boxers.

- Ischemic cerebrovascular events do not have strong breed, sex, or age correlation but been observed more commonly in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Greyhounds.

While signalment can help guide suspicion, it is also important to recognize that signalment can foster bias in clinical reasoning so should only play a small part in the development a differential list.

History

As with signalment, being able to obtain an accurate and complete medical history is an invaluable skill for a veterinarian. In cases of suspected forebrain disease, it can also be a key piece of the puzzle. The main function of the forebrain is sensory information processing and behavior; therefore, disease can manifest as subtle personality or behavior change. Examples include decreased interaction with the owner, pacing or wandering, loss of normal learned behaviors, or episodes of disorientation. The identification of these clinical signs outside the times of reported seizure activity should increase concern for structural disease. History can also help to identify co-morbidities which may affect the patient’s overall prognosis or risk of complications with further diagnostics and treatment.

Neurologic Examination

The neurologic examination is yet another tool for identifying those patients with a higher concern for structural disease. In one study looking at dogs older that five years of age (Schwartz et al. 2013), the neurologic examination had a sensitivity and specificity of 74 and 62% respectively for identifying secondary epilepsy (seizures caused by structural or reactive etiologies). So while helpful, the neurologic exam is by no means perfect as many animals can have lesions in “silent” cortical regions of the brain that remain undetectable by examination. The neurologic examination has a reported 55% negative predictive value, meaning a normal exam by no means excludes the possibility of structural or reactive epilepsy.

Post-ictal changes, which can include change in mentation, proprioceptive deficits with ataxia, decreased menace response, and decreased response to noxious nasal stimulation are more likely to present as symmetrical deficits, observed following the seizure event, and gradually resolve as the seizures become controlled. Persistent asymmetry of signs or cranial nerve deficits other than menace and noxious nasal stimulation should prompt concern for structural disease.

Table 1. Example of a differential list for seizure etiology according to age group.

Diagnostic Testing for Adult Onset Seizures in Dogs and Cats

Initial diagnostic testing in any patient presenting with new onset seizures should include baseline bloodwork (CBC/Chemistry). Bloodwork is used to help rule in/out causes for reactive seizures, identify co-morbidities that may affect further diagnostic or treatment choices, and document a baseline for monitoring if starting anticonvulsant medication.

Further diagnostics choices are then guided by clinical reasoning. For many senior animals this may include thoracic radiographs +/- abdominal imaging.

Three view thoracic radiographs are recommended prior to MRI to screen for cardiopulmonary disease and metastatic disease. Abdominal ultrasound may be recommended if there is concern for abdominal disease from clinical history, physical exam, or bloodwork.

In cats, lymphoma is the second most common intracranial neoplasia after meningioma. Lymphoma can often be a multicentric process so may be found through abdominal imaging and sampling. Hemangiosarcoma is the most common metastatic tumor to the canine brain, with other commonly affected sites including the lung, liver, heart, kidney, and spleen. After these initial screening tests are performed, the remaining diagnostics include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain +/- CSF analysis to determine if there is intracranial pathology.

While ideally, we would want many of our senior onset seizure cases to pursue diagnosis, cost associated with further testing as well as concern regarding anesthesia and long-term outcomes often result in clients declining advanced diagnostics. In these cases, history and exam become important in providing clients with guidance regarding treatment. New onset seizures in senior animals may have a variety of underlying causes with variable prognoses. Many of these cases can be managed successfully with supportive care and continued monitoring.

Treatment Strategies for Adult Onset Seizures in Dogs and Cats

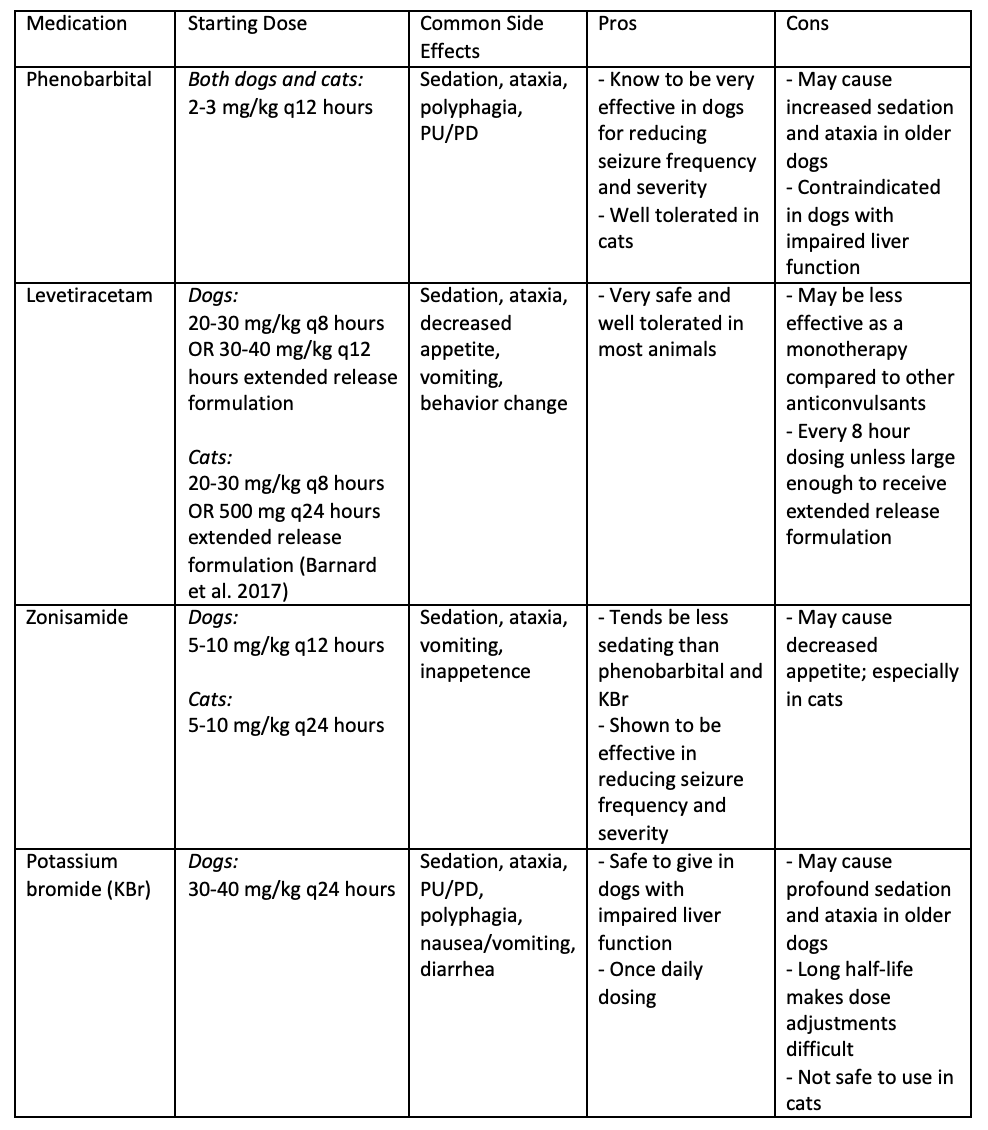

While the specifics of when and how to best treat seizures are still debated, there are some general principles to follow. In any case demonstrating status epilepticus (seizure lasting > five minutes) or cluster seizures (≥two seizures within 24 hours), treatment with an anticonvulsant therapy should be started. If there are signs of structural disease, either in the patient’s history or neurologic exam, treatment with an anticonvulsant is also highly recommended. The type of anticonvulsant used will depend on your patient and your client. If there are no contraindications for your patient, then educating the client on their options and leaving the choice to them can often increase satisfaction and compliance (see Table 2 for a brief summary on available anticonvulsants).

In cases where clients decline referral and there is a concern for structural epilepsy, there are other available treatment options. Ideally before these are pursued, baseline bloodwork would be performed to rule out any obvious changes indicating disease elsewhere in the body. If bloodwork is normal and the patient has a normal neurologic examination, serial examinations +/- treatment with an anticonvulsant may be sufficient. If there is concern for structural brain disease, the owner should be educated on the possible causes and outcomes.

Neoplasia is one of the more common causes of new onset seizures in older animals. Treatment of diagnostically confirmed CNS neoplasia often includes surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy with variable responses depending on location and type. Palliative treatment with an anti-inflammatory dose of steroid (prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg/day) can help to reduce clinical signs and improve quality of life for a short time. If empirically treating with a steroid it is important to educate owners of the side effects, that there is risk of relapse or worsening of clinical signs over time, and prior administration of a steroid may make future diagnosis or treatment more difficult if the client elects to pursue referral after starting this medication.

Ischemic cerebrovascular events often have a per-acute onset, lateralized neurologic deficits, and show gradual improvement or stabilization of disease with time. Management of these cases is through treatment of underlying disease if identified (e.g. cardiovascular disease, Cushing’s, hyperthyroidism, etc…) and supportive care.

Multifocal neurologic deficits and progressive disease may increase concern for meningoencephalitis. In these cases, treatment with an encephalitis protocol can be started which often includes an anti-inflammatory dose of steroid in addition to antibiotics and/or antifungal therapy based on the common CNS infectious diseases in your region or based on the patient’s travel history.

Table 2. Common anticonvulsant medications: dose, side effects, and pros/cons with use in senior onset epilepsy.

In any case where there is concern for increased intracranial pressure, treatment with mannitol or hypertonic saline should also be considered. One of the earliest signs of increased intracranial pressure is a decreased level of mentation. Other signs may include loss of brainstem functions such as cranial nerve deficits, tetraparesis, and respiratory or cardiovascular changes.

References

Barnard L, Barnes Heller H, Boothe DM. Pharmacokinetics of Single Oral Dose Extended-Release Levetiracetam in Healthy Cats. J Vet Intern Med 2017; 32 (1): 348-351.

Bhatti SF, De Risio L, Muñana K et al. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: medical treatment of canine epilepsy in Europe. BMC Vet Res 2015; 11: 176.

Ghormley TM, Feldman DG, Cook JR Jr. Epilepsy in dogs five years of age and older: 99 cases (2006-2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015; 246 (4): 447-450.

Mandara MT, Motta L, Calò P. Distribution of feline lymphoma in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Vet J 2016; 216: 109-116.

Schwartz M, Muñana KR, Nettifee-Osborne J. Assessment of prevalence and clinical features of cryptogenic epilepsy in dogs: 45 cases (2003-2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013; 242(5): 651-657.

Snyder JM, Lipitz L, Skorupski KA, Shofer FS, Van Winkle TJ. Secondary intracranial neoplasia in thedog: 177 cases (1986-2003). J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22 (1): 172-177.

Pákozdy A, Leschnik M, Sarchahi AA, Tichy AG, Thalhammer JG. Clinical comparison of primary versus secondary epilepsy in 125 cats. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12(12): 910-916.

Podell M. Seizures. In: PlattS. and Olby N. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology. 2012; 210-211.